Inflation is the talk of the town. In recent months it has started to rise, leading to some speculation that we are heading back to the 1970s – when inflation peaked at 25%. John Butters, Chief Investment Officer, talks to Paul Dales, Chief UK Economist at Capital Economics, to get his views on whether much higher inflation is on the cards.

Key points:

- Inflation is rising faster than expected.

- Inflation to reach 4%, but spike will be short-lived.

- 1970s style inflation will be avoided.

Did you foresee the recent spike in inflation?

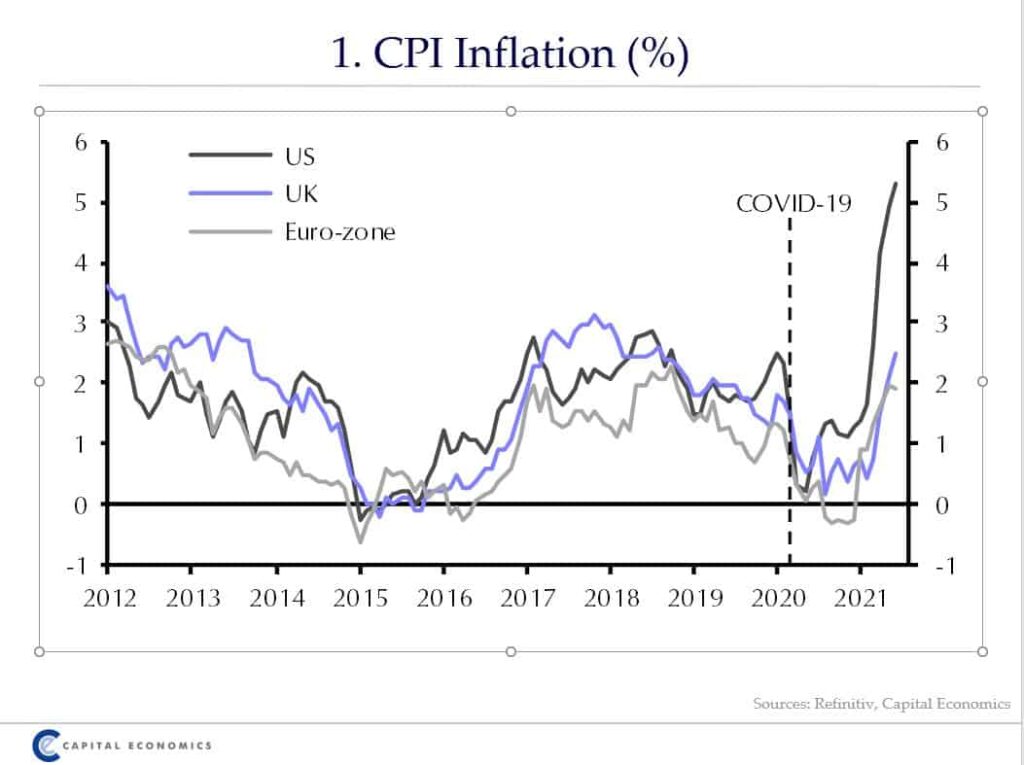

When we spoke last time in November, I said there was a lot of upside risks to higher inflation as economies began to recover from the coronavirus crisis – but I have been surprised at how quickly this has started to come through. Inflation in the US is the most striking but even in the UK, inflation has started to pick up above the target of 2%.

Are we going to go back to the 1970s era of extreme inflation?

Inflation has been largely dull over the past 20-30 years, averaging around 2% in the UK, which is a far cry from the 1970s when the average rate of inflation was 9% – in August 1975, it was incredibly high at 25.3%. But it was a different time back then – trade unions were prevalent, which tended to bid up wages, while central banks weren’t trying to control inflation as they are today.

When you come to assessing what’s going to happen to inflation, you need to look at two themes: the structural factors (how central banks are looking to control it) and the cyclical factors, such as the strength of the economy and whether that’s going to push up on inflation in the near term. And it’s the cyclical factor which I believe is the crunch. How big is this cyclical uptrend going to be as economies recover from the pandemic? Is that going to generate inflation? And if so, how long is it going to last?

Why might the so-called base effect be distorting the real rate of inflation?

Inflation is calculated as the percentage change in the level of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in one period, compared to the level a year earlier. So, the current inflation rate is determined just as much by what happened a year ago, as it is by what happens now. At the height of the pandemic in 2020 the CPI was unusually low as consumer spending dropped dramatically. This has caused year-on-year comparisons to be exaggerated – and they will be until such time that last year’s spring lows fall away from the calculations. So, in other words, as long as the CPI rises at just a normal rate, inflation will rise from around 2% to around 3% by the start of next year. That’s just a mathematical quirk that’s built into the figures – it’s going to look like there’s a lot more inflation than there actually is.

I suspect that after including the base effect and the effects of food price increases, we will see CPI inflation peak around 4% by the end of this year. This is still quite a big deal – not compared to the 1970s but compared to the past 20 years and it would be double the Bank of England’s inflation 2% target.

How long will higher inflation persist?

It will depend on several factors. Base effects are temporary, similarly changes in the level of prices generated by supply shortages tend to last for only a year or two as well. The risk, though, is that the current trend becomes more self-sustaining. That can happen if higher inflation feeds through into pay growth and/or inflation expectations. Once people’s pay starts rising at a faster rate, then they’ve got more spending power and they can spend more. Subsequently, businesses can put up their prices more. The same can happen with inflation expectations. If inflation is expected to permanently shift up, simply because people expect inflation to be higher, it will be because businesses know they can raise prices – and people know that they can hopefully get a wage increase that compensates them. Another factor is whether the economic recovery is going to be so strong that it just generates inflation everywhere.

What is the likelihood that these risks will materialise?

They are risks but I don’t think they are going to materialise. If we look at pay growth, I’m not convinced there’s going to be a huge, permanent, sustained surge in pay growth. Average earnings growth this year has risen but this is again due to a base effect, so comparing to wages last year. And, for example, those people who have been unfortunate enough to lose their job over the last year have been, by and large, low paid workers. Take them out and the average level of earnings goes up. That doesn’t mean those people who’ve kept their jobs have been getting hefty pay rises.

Some statistical measures show that inflation expectations have edged up, but I don’t think you can conclude that there’s been a step change higher. Expectations are still only slightly above the average rate of inflation over the last decade. I’d be surprised if inflation expectations move significantly higher over the next couple of years.

The backdrop for the economic situation is going to be somewhat fragile. Recoveries have been quite strong but haven’t yet got back to a level of economic activity that we enjoyed before the pandemic started. This leads me to believe that inflation will rise quite sharply over the next six to nine months – I’d stress that that’s probably going to be a bigger increase than most people are expecting due to the recent rises in commodity and component costs. However, I do think it will be short lived if we’re not getting much pay growth and we’re not getting a rise in inflation expectations. For my money, we’re going to get a rise in inflation, but it’s going to last for perhaps a year or so before it starts to fall back down again.

Will the Bank of England raise interest rates?

If you examine the period after the 2008 Financial Crisis, the Bank held off raising rates when inflation started to rise because it felt it was going to be short-lived – even though it got flack for doing so. I think it’s going to be a similar situation this time. I suspect some people on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee may vote to raise interest rates. But my feeling is that the Committee, as a whole, will decide that this spike in inflation isn’t worth responding to because it’s a temporary, rather than a permanent change. Our forecast is that the Bank will keep interest rates on hold throughout 2022 and probably throughout 2023 as well.

That said, there will likely be higher interest rates at some point. We’ve got a situation where economic demand has been lowered significantly by the pandemic and supply has been lowered as well. But our sense is that over the next couple of years, economic supply is going to be greater than economic demand. In other words, there’s some room for the economy to run a little bit hot before you bump up against these supply capacities, where businesses just can’t meet the orders and raise prices just to boost revenues. It’s at that point, that you will likely start getting a sustained rise in inflation above the target and where wage growth does genuinely start to pick up.

If central banks just stick wholeheartedly to the current inflation targeting system, then I suspect they’ll just raise interest rates or tighten policy by shrinking balance sheets, which will bring inflation back down on average to 2% for the next couple of years. However, there is a possibility that central banks may go a little bit soft on inflation – they or governments may decide a bit more inflation, around 2.5%, might be a good thing.

What does it mean for clients of Weatherbys Private Bank?

At Weatherbys we build portfolios that make sense in the economic regime as it is now, rather than based on forecasts. We make decisions in our portfolio construction for our global tracker portfolios based on the structure of the economy. If that structure changes and inflation does start to become a problem, we believe that will happen slowly and, so, we’ll be able to see it happening. We will then adjust portfolios in response to that new reality. But for now, we are relaxed.

We continue to believe that equities are the best place to be. There is no investment asset that reliably protects against inflation in the short term, but many studies highlight that equities, over the long term, tend to outpace inflation. However, it’s important to be aware that not all equities are the same, and depending on the environment, some stocks will fare better than others. Prices of high-quality bonds can rise during periods of deflation and so offer some protection against falling prices.

The overriding message is to stay diversified and balanced in your investment portfolio. And be prepared to take a step up the risk ladder by investing in equities because staying in the perceived safety of cash is a risk – even when inflation remains subdued.

Important information:

Capital Economics is an independent consultancy firm. Past performance is not a guide to future returns. Please note that the value of investments can go down as well as up, and you may get back less than you originally invested.