But it is sometimes argued that a selective approach comes into its own when stocks take a tumble – a discriminating manager can, it is claimed, insulate investors from the worst of precipitous falls.

If true, it would be a compelling reason to switch out of low-cost index trackers and into active managers – especially right now, with stocks ostensibly expensive and an “AI bubble” supposedly about to pop.

A look at the data

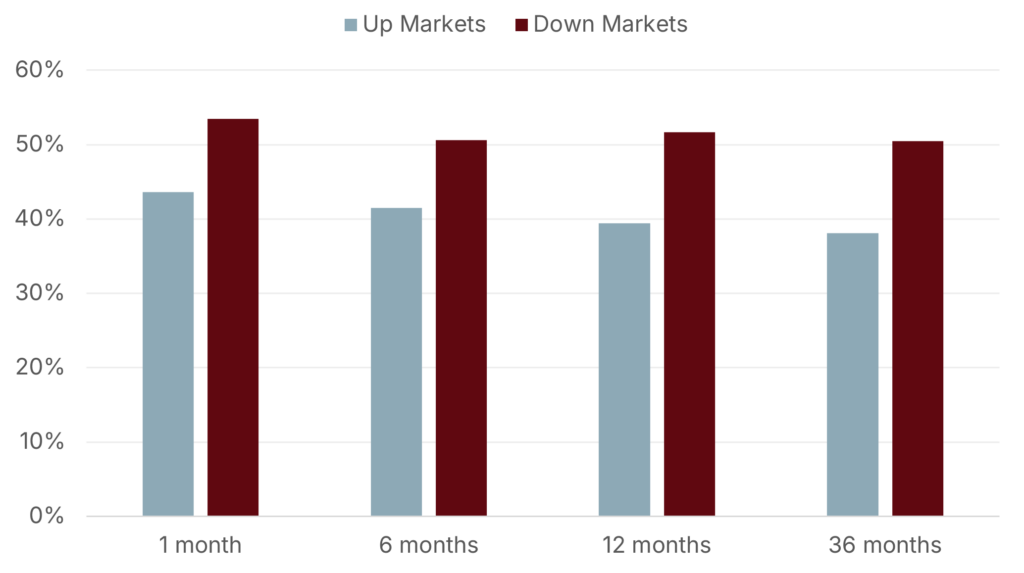

A recent article by The Evidence-Based Investor[1] offers an insightful review of 26 years’ worth of fund performance data to find out if there is any truth to the notion. Jeffrey Ptak of Morningstar[2] found that, sure enough, actively managed US equity funds have historically outperformed in down markets – but only very marginally.

Active US equity funds: average success rates

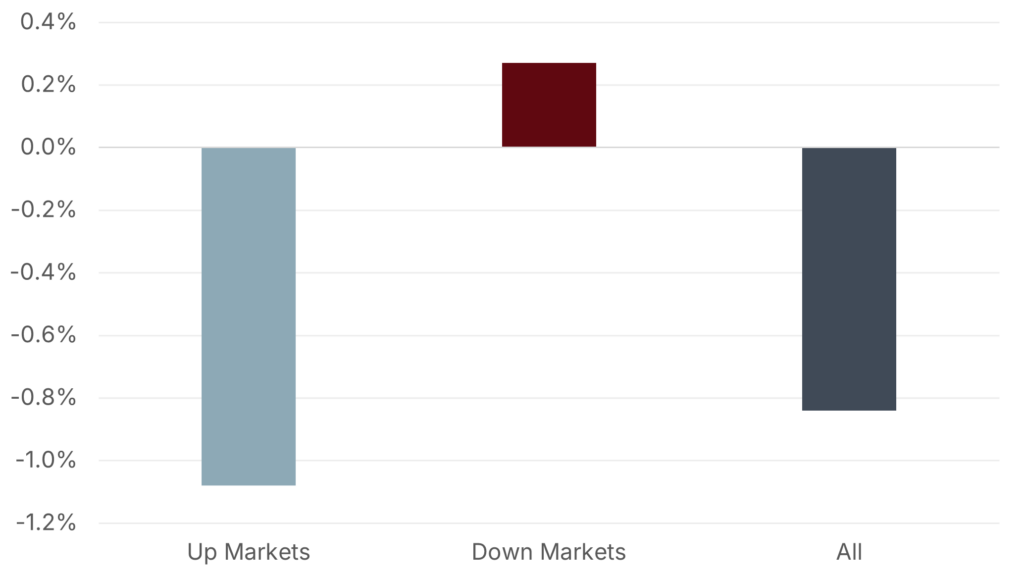

The problem is that the rest of the time – the vast majority of the time – stock-pickers have fared poorly. Those brief flickers of downside prowess have been both too few and too small to compensate.

Active US equity funds: average 36-month excess return

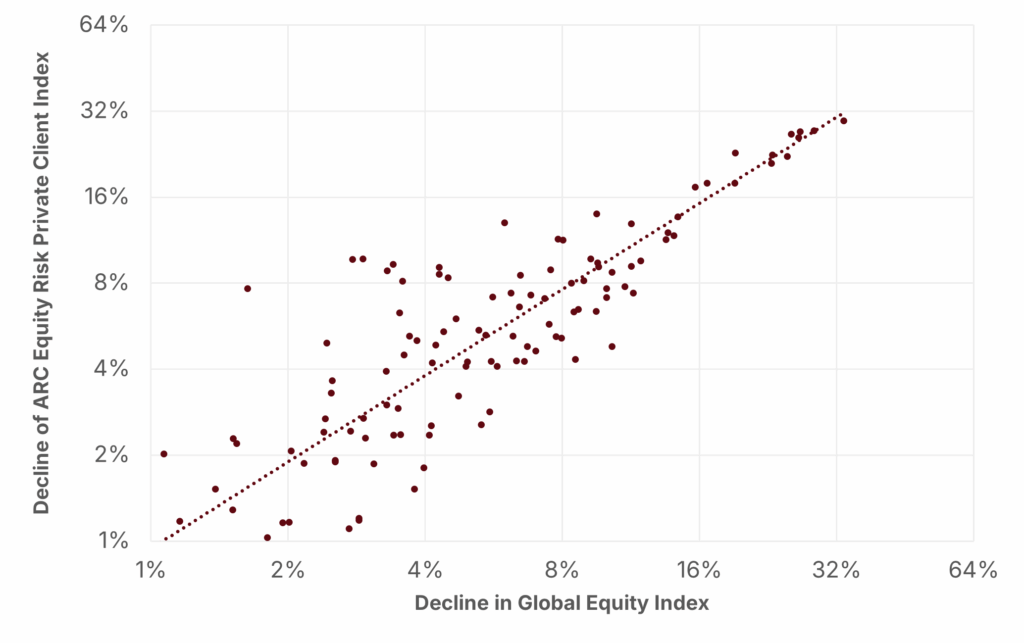

Perhaps a more relevant set of data comes from Asset Risk Consultants (ARC), an independent firm which aggregates the performance of real private client portfolios[3].

Using monthly returns data going back to 2004, we can see how the typical actively-managed equity portfolio performed when stock markets fell. The overall pattern seems to be that these portfolios have declined by roughly as much as broader market, but there are times when stock-pickers have done considerably better than a passive strategy, and other times worse.

And this is before we even consider the dispersion across different managers that is obscured by aggregating them into one single private client index.

In summary, the data seems to offer a vindication of the idea that active managers can protect investors from market shocks, but it is far from clear-cut – they have on occasion done worse.

Might active managers fare better in future?

We should not read too much into historical data. After all, past performance really is not a guide to the future. Explanations are far more important, and durable, than evidence – because the latter requires interpretation. Patterns can be spurious, and trends ephemeral.

For instance, it is well-known that most investment portfolios here in Britain – even those offered by multi-national, foreign firms – have a pronounced bias in favour of UK assets. Indeed, this is a big part of why they have performed so badly over the past decade or so.

We should therefore reasonably expect portfolios with this bias to enjoy their day in the sun should the US underperform, and/or the dollar weaken. As a matter of fact, this is precisely what happened early in 2025, when President Trump unveiled his Liberation Day tariffs.

Nevertheless, the typical private client equity portfolio has underperformed a simple global index tracker – despite US equities failing to catch up with the FTSE in sterling terms. The reason seems to be that wariness of US tech firms has wiped out any benefit from a bias in favour of the FTSE.

What if the AI bubble bursts?

If stock-pickers have spent the past few years rationalising their decisions to under-allocate to the darlings of the Large Language Model revolution, surely this would finally come good if the sky fell in?

Quite probably, yes. However, we cannot be sure, because as the example above illustrates, it depends on how the rest of an actively managed portfolio performs. These portfolios usually tend to be quite concentrated, and so it only takes one or two duds to cancel out a good call made elsewhere.

Plus – and this cannot be overstated enough – the original decision to steer clear of those more speculative US firms has cost stock-pickers dearly in terms of forfeited gains. If there is eventually some sort of tech reckoning, it may well turn out to be a mere pothole compared to the mountain markets have ascended.

Summary

Historical performance suggests that stock-pickers have enjoyed marginally superior returns on the relatively few occasions when markets have taken a dip. But this has not been enough to compensate for their underperformance the rest of the time. That said, a backwards-looking approach isn’t terribly helpful.

Looking ahead, the general point is that we cannot say for sure whether active managers will outperform in future downturns, because the nature of the downturn matters, as well as what those stock-pickers have been doing in the rest of their portfolios.

The broader point is that we do not invest in downturns. We invest for the longer term, including the ups and downs. It makes no sense to optimise for only one side of this equation.

Far better to work out what degree of decline one can stomach – both mentally and in terms of one’s financial circumstances – and avoid the temptation to try to outmanoeuvre the rest of the world.

Important information

Investments can go up and down in value and you may not get back the full amount you invest.

[1] https://www.evidenceinvestor.com/post/active-funds-in-downturns

[2] https://www.morningstar.com/funds/active-funds-fare-better-downturns-its-still-not-enough

[3] ARC Research, now a part of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC www.suggestus.com