The sums involved are enormous. Japanese investors hold around $1.1 trillion in US Treasuries, making Japan the single largest foreign owner of the world’s largest pile of government debt. For years, that money stayed put because US yields were simply in another league compared with Japan’s.

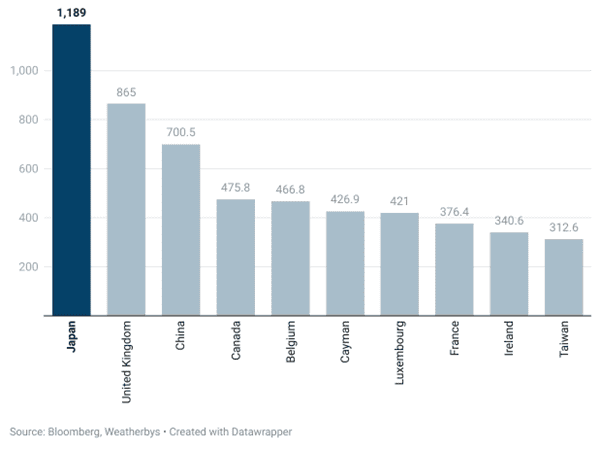

Japan is the largest foreign owner of US Treasuries

Chart show amount of US Treasuries owned by investors in each territory in billions of dollars

That gap has started to close. US yields have eased from their peaks, while Japanese yields have finally lifted from below the zero bound. The difference that once looked permanent now looks temporary, and the idea of money flowing back to Tokyo no longer seems far-fetched.

Self-regulating systems

The nightmare version of events is easy to imagine. If that capital rushed home all at once, Treasury prices would fall and yields would jump, pushing up borrowing costs across the US economy. Mortgage rates would rise, asset prices would wobble, and recession fears would quickly follow. In a market already nervous about deficits and heavy debt issuance, that would be genuinely destabilising.

But this fear assumes a system that feeds on itself. The Japan–US yield story does not. As money leaves Treasuries, US yields rise. As that same money flows into Japanese government bonds, their yields fall. The very act of moving capital dulls the incentive to keep moving it. As the chart below shows, the difference between US and Japanese yields has been considerably smaller in the past, without resulting in large-scale Treasury disinvestment.

Narrower yield spread has not deterred Japanese investors

A smaller difference between US and Japanese yields have not resulted in a decline in Japanese ownership of US Treasuries

In the language of systems theory, this is the difference between mechanisms that regulate themselves and those that self-perpetuate. Both types occur in the real world outside finance.

On the one hand, animal populations stop growing when food or space runs out. Traffic jams thin out as delays push drivers to alternative routes or times. These systems may be chaotic, but they rarely spiral out of control because pressure creates pushback.

On the other are systems that lead to exponential growth. Snowballs get bigger as they roll downhill. Fires intensify as heat dries surrounding foliage, creating more fuel. In finance, compound interest works the same way, which is why Warren Buffett compared wealth-building to a snowball that becomes harder to stop the longer it rolls.

Yield mechanics

Cross-border yield differentials don’t snowball. The easiest way to see this is to understand how fixed-income instruments work. Unlike shares, Treasuries and Japanese government bonds have a fixed end point. A bond that matures in one year at $100 and trades today at $90 offers a return of about 10 per cent. If demand pushes that price up to $95, it still matures at $100, but the return falls to roughly 5 per cent.

In other words, buying a bond makes it less attractive for the next buyer. Selling does the opposite. That built-in feedback is why inter-market bond trades tend to cool their own excesses rather than amplify them.

None of this means Japan’s shift is irrelevant. A healthier economy and higher domestic yields will reshape flows at the margin, affecting currencies, hedging costs, and asset prices over time. As Japanese yields rise, there are real and troubling consequences for those who borrowed in that market to reinvest in risky assets such as cryptocurrencies or AI stocks.

But it does mean this is not the kind of risk that demands panic or wholesale reallocation. Compared with genuinely self-reinforcing dangers elsewhere in markets, the convergence of Japanese and US yields looks less like the start of a crisis and more like the system doing what it is designed to do.

Important information

This article does not constitute advice. The value of bonds can go down as well as up.