The UK’s latest consumer-prices reading surprised even hardened market watchers, ticking upwards to an annualised rate of 3.8 per cent, nearly double the Bank of England’s target. Even stripping out volatile elements like food and energy makes no difference. Instead, persistently sharp price rises in the services sector suggest the new normal is here to stay.

Walk into any supermarket, and it almost hurts — the same basket you bought last year feels like it has been swapped for champagne and truffles. You’re still holding bread and milk, but your wallet screams otherwise. That has implications for savers as much as it does for spenders. And it’s feeding through into global markets.

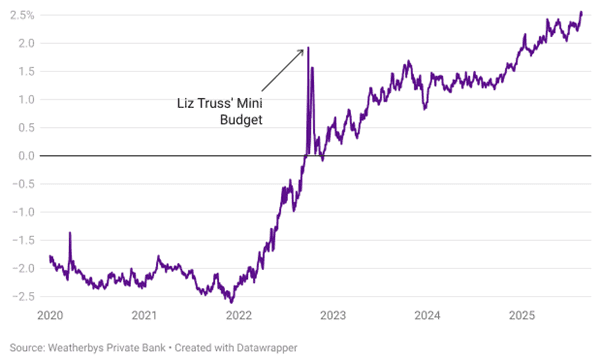

The yield on 30-year UK government bonds has surged to 5.6 per cent, a level not seen since 1998 – nearly a percentage point higher than during the market turmoil of October 2022, when Liz Truss’ mini‑budget crisis rattled investors. And that was even before traders learned the general price level was rising at the fastest annual pace in 18 months, driven in part by a 30 per cent jump in airfares (with the timing of school holidays a factor), higher motor fuel costs, and a fourth consecutive monthly increase in food costs. Yields on longer-dated bonds that specifically have their values linked to inflation also jumped.

Yields soar

The UK 30-year inflation-linked bond yield hit highs seen in 1998. Nominal yields also climbed.

Bank rate conundrum

And it’s against this backdrop that Threadneedle Street is starting to contemplate easing off the accelerator. Since mid‑2024, Governor Andrew Bailey and his team have trimmed rates by 1.25 percentage points. Over the coming year, traders expect that pace to moderate.

When inflation quickens, central banks would generally like to raise interest rates, thereby cutting demand and easing price pressures — but steeper borrowing costs also choke off credit, investment and household spending. That’s the conundrum: taming prices without strangling the very growth it’s meant to safeguard.

And it’s not just a UK phenomenon either. In the US, President Donald Trump’s tariff push means the cost of goods may trend higher in coming months.

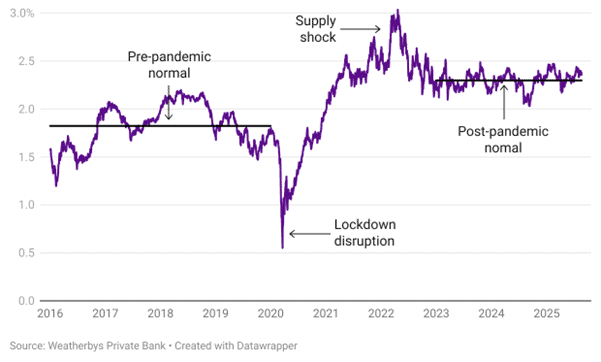

Breakeven rates and market sentiment

Breakeven rates — the gap between yields on conventional government bonds and yields on inflation‑linked securities — are a widely used proxy for market expectations of future inflation. While they’re not a perfect forecast, they distil the collective judgement of bond investors on the likely path of prices.

Expecting inflation

The UK 30-year inflation-linked bond yield hit highs seen in 1998. National yields also climbed.

Before the pandemic, long‑term US breakevens typically sat below 2 per cent, in line with the Federal Reserve’s target. Since 2020, they have remained persistently higher. This shift suggests that markets no longer believe central banks can keep inflation anchored within target ranges.

US trends: The stubborn core

Recent US Consumer Price Index data shows headline inflation moderating, but core data — which strips out volatile food and energy — still running above 3 per cent. Core inflation is often “stickier” because it reflects slower‑moving forces like wage growth and service‑sector demand.

A closer look at the components reveals that services inflation is ticking higher, driven by rising pay in healthcare, hospitality and other labour‑intensive sectors. Goods inflation, which surged during the pandemic amid supply chain chaos, has eased but remains a potential swing factor. The threat of renewed tariffs could push goods prices higher again if companies pass on costs to consumers.

Historical perspective: Lessons from the Volcker era

The US experience in the late 1970s and early 1980s remains a cautionary tale. The Fed initially hesitated to raise rates aggressively, allowing inflation expectations to become entrenched. Chair Paul Volcker’s eventual cure — double‑digit interest rates — inflicted a deep recession.

The parallel today is not exact, but the message is clear: central banks that move too slowly risk losing credibility, forcing harsher action later. For the UK, the combination of above‑target inflation and surging long‑term yields is a reminder that markets can quickly punish perceived complacency.

Looking ahead: Jackson hole and beyond

The upcoming Jackson Hole symposium – a meeting of central bankers in Wyoming – will be closely watched for signals. Markets are currently pricing in up to five Fed rate cuts by the end of 2026, but any hint of caution could trigger volatility. In the UK, the next Bank of England rate decision on 18 September will weigh domestic inflation pressures against a slowing labour market and fragile growth.

For policymakers, the challenge is to steer inflation back to target without triggering a downturn. For savers and investors, inflation-protected securities may start to look more attractive.

Important information

This article does not constitute advice. The value of gilts can go down as well as up.